UK: National identity in Britain

The union of Britain and Northern Ireland is under threat. Can any of our political parties hold it together?

At its core, British identity is a combination of three national identities; English, Welsh, and Scottish. Added to this mix are the numerous other national identities of immigrant communities. At times throughout history these identities have coexisted under one British identity harmoniously. At other times, tension between these identities has had deadly consequences.

Two general elections, one in the UK and one in Ireland, have once again thrown the issue of the future of the union into sharp relief. Matters of identity, nationality, and patriotism are now key to understanding the current state of British politics. In this context, we thought it might be worth looking at how people living in Britain identify when it comes to nationhood.

It’s worth saying that for this research, we concentrated on identity relating to the countries that make up Great Britain (not the UK); Scotland, Wales and England. Northern Ireland, with its own unique experience of nationalism, needs its own dedicated study, as does the national identity of people with connections to other areas of the globe. Watch this space…

Britain

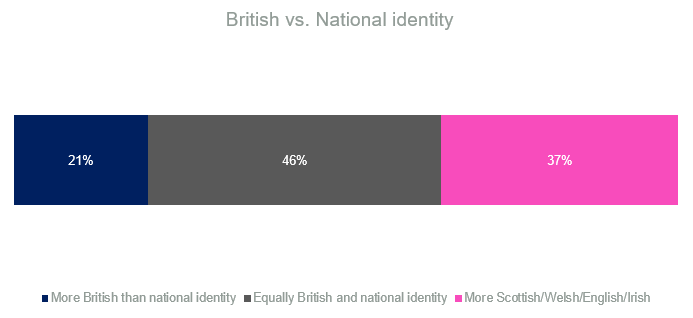

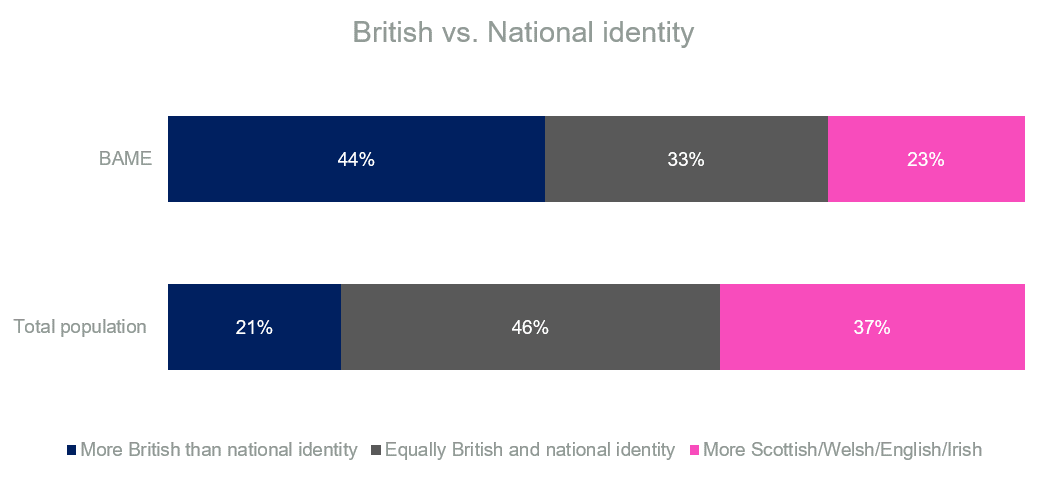

At a total level, most people living in Britain say that they identify equally with their British and their national identity. Almost half, (46%), say this is the case, followed by 37% who identify more with a Scottish/Welsh/English/Irish identity, and 21% who identify more as British.

However, interesting regional and cultural differences emerge. For example, those living in London are more likely to say that Britishness trumps their national identity (33% vs. 29%). This is most likely a reflection of the city’s cosmopolitan and multicultural demographics. Those from BAME backgrounds are more likely to say that British is more of an identity for them compared to English, Welsh, or Scottish. It makes sense that as citizens with a multiplicity of identities, ethnic minorities are more likely to collapse their identity under a larger “British” umbrella.

England

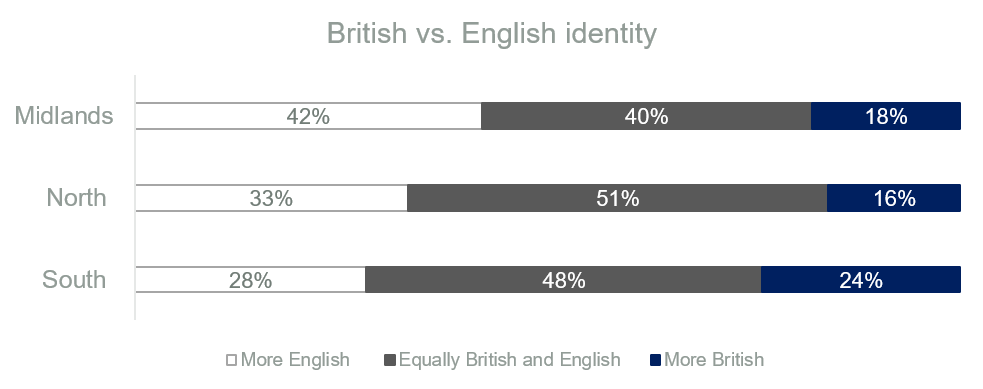

In England, we also see interesting regional differences. Those living in the North and the Midlands are more likely than those in the South to say they are more English than British (this remains the case even when we exclude London from the South East).

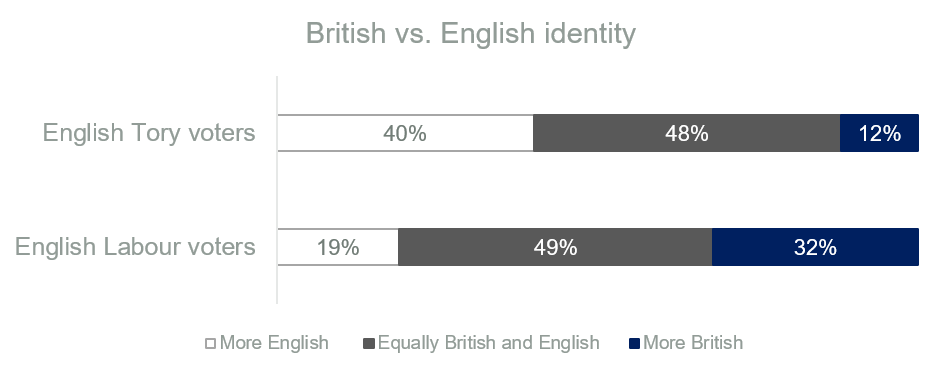

This is especially pertinent given that the election in December was defined by a Tory party that captured great swathes of England, particularly those so-called red-wall seats. How much did patriotism play a part? Let’s take a look at Labour voters in England vs. Conservative voters in England. English Tories are much more likely to identify strongly with Englishness than English Labour voters. As the chart below shows, 40% of Tory voters living in England say they are more English then British compared to only 19% of Labour voters.

Wales

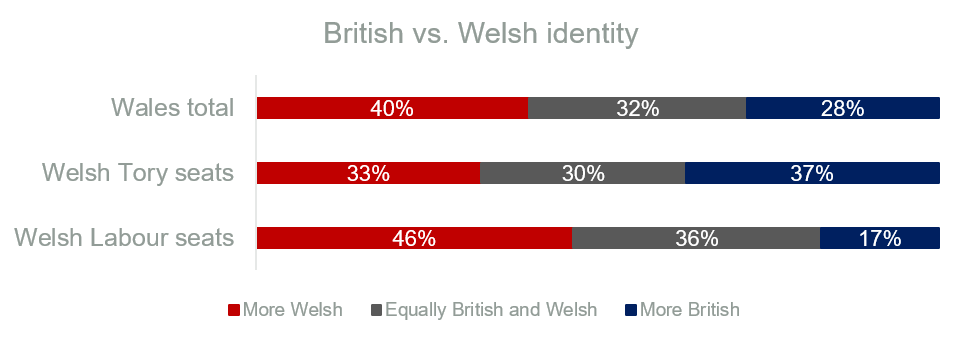

In Wales, a fascinating pattern emerges. In Labour constituencies like Newport South and Pontypridd in the old industrial south, 46% identify as more Welsh than British, with only 17% saying the opposite. This contrasts with Conservative constituencies, like Preseli Pembrokeshire and Montgomeryshire, where 37% identify as more British than Welsh. In terms of national identity and voting behaviour, we see a reverse of the pattern in England.

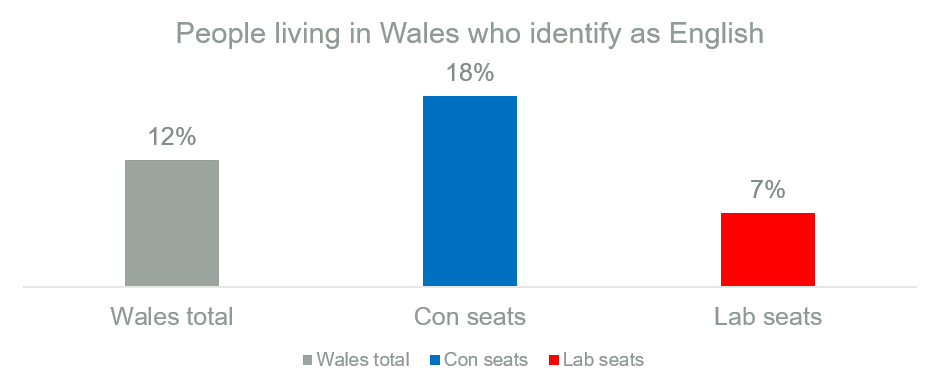

Interestingly, 18% of those living in these Welsh Tory seats also identify as English compared only 7% in Labour seats.

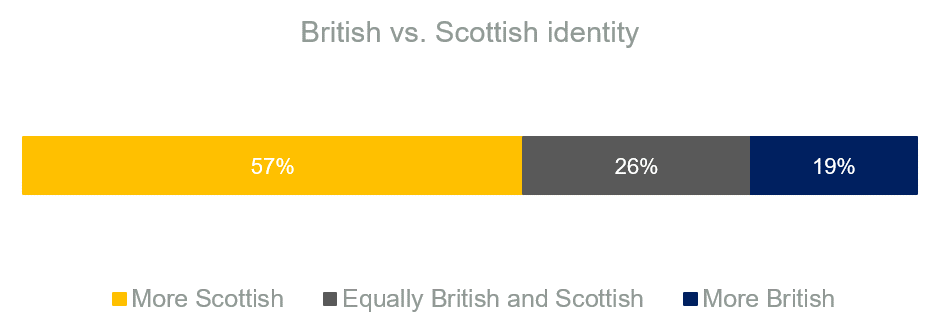

Scotland

And in Scotland? Perhaps unsurprisingly, an overwhelming nationalist sentiment dominates. Over half, (56%), of Scots say they identify with Scottishness more than Britishness.

What does this mean for the union?

The big picture is an important one. The party that has “unionist” in its name, The Conservatives, have become the party of England with a peculiar appendage of Anglophile Wales. Meanwhile, Labour represents the cities of England and Wales, and Scotland has been captured by the SNP. Across the Irish Sea, a united Ireland is becoming an increasingly probable future.

What does this mean for the union? Who are the party of Britain and the UK? And how do they hold it together? These are just some of the questions that these figures raise. The challenge for our political parties is turning a message of British unity into a successful electoral strategy. Whether we’ll see this in the near future is another question.