How should Labour approach Brexit? Keep their options open

Adam Drummond: Labour’s strategic vagueness worked in 2017 and ‘sane Brexit’ is their best chance of keeping their options open until we know how things are turning out.

Rather than being wiping them out as many expected, the 2017 general election saw Labour increasing their number of seats and significantly increasing their vote share to 40%, a level not seen since Tony Blair in 2001.

Why was this? Because Labour’s Brexit policy of strategic vagueness worked. Jeremy Corbyn’s controversial decision to whip Labour MPs to vote to trigger Article 50 neutralised Brexit as an election issue, taking away Theresa May’s strongest asset. Labour’s losses among Leave voters were not as large as many in the party had feared while the Conservatives’ de facto rebranding as the Brexit party meant that many Remainers flocked to Labour as the best option to resist that, particularly after the Liberal Democrats failed to take off.

While it is correct to point out that Leave voters who distrust Labour on the EU are a potential source of further growth, the actions Labour would need to take to reassure this group are not cost free, as Theresa May found out.

Labour embracing Brexit is difficult, for two reasons.

The first is that the main source of Labour gains between 2015 and 2017 were among social liberals and younger voters, particularly those aged 25-44. Compared to 18-24 year olds who one could always expect to give Labour their support, the percentage of this ?young from an MP?s perspective? group voting Labour went from 33% to 48% for 25-34s and from 28% to 37% for 35-44s.

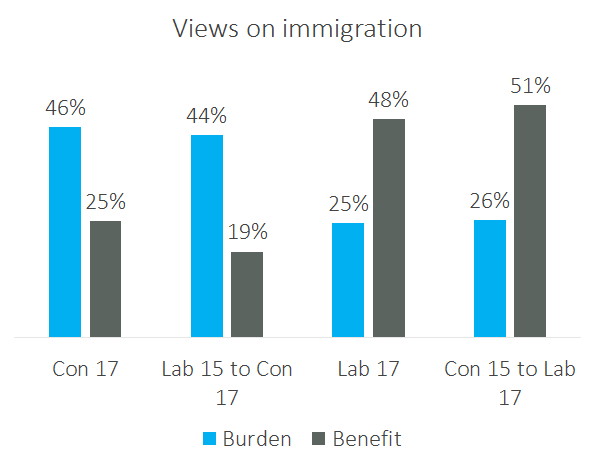

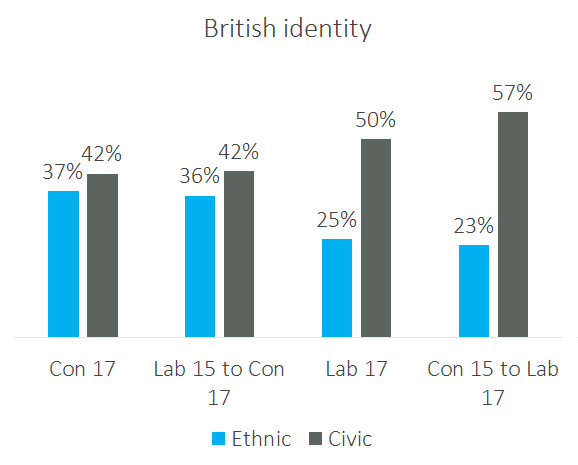

Between 2015 and 2017 the Tories lost significant ground among those who think immigration is a benefit rather than a burden, and among those who say ?British? is a civic identity that can be adopted as opposed to something you have to be born with. Two key factors we use in our political tribes segmentation to identify social liberalism. Similarly, Labour?s share of the graduate vote increased from 29% in 2015 to 41% in 2017.

This group generally voted Remain and were significantly put off by Theresa May?s ?citizens of nowhere? approach to Brexit. While they could see themselves as people who?d vote for David Cameron’s party which legalised same sex marriage and ring-fenced foreign aid, they weren’t going to vote for a UKIP-light approach that sounded like it would bring back grammar schools and fox hunting and saw immigrants as guilty until proven innocent.

Theresa May?s embrace of former UKIP voters alienated this group and Labour should be extremely careful about its approach to Brexit, particularly if Vince Cable proves to be a more credible Liberal Democrat leader than Tim Farron.

But the second, more important issue is that there is a reason why the vast majority of Labour MPs, members and activists (not to mention a slight majority of Conservative MPs) opposed Brexit in the first place: because they think it?s a bad idea.

Let’s game out some scenarios:

- Brexit is a spectacular success (or at least net neutral).

- Brexit is a long term success (or, again, at least net neutral) but involves a degree of short term economic pain.

- Brexit is a longer term disaster that involves significant economic and political damage to the country.

In scenario a) Brexit ceases to be a dividing issue, those who backed it are vindicated, a new consensus forms and Labour adapts to this in the way that New Labour accepted the Thatcherite consensus in the 1990s.

In scenarios b) and c) the government pays an electoral price for getting the country into such a situation this and Labour need to be able to say ?this is because of Conservative actions and policy?, something they cannot credible say if they have supported the approach which got us there.

Which scenario we are in is at the moment unknown. A plurality disapprove of how the process is being handled and the chances of a final Brexit deal both satisfying the (often conflicting) demands of Leave voters and avoiding significant economic harm are minimal.

Labour cannot credibly become ?the Brexit party? until there is a clear consensus in favour, something that is unlikely to happen soon given the age breakdown of the Leave vote. But they also cannot simply ignore the issue forever given its size. The best option therefore is to advocate ?sane Brexit?, ?sensible Brexit? or even ?Jobs first Brexit?, demanding all the benefits the Leave campaign promised while leaving the government to navigate the difficult trade-offs that the process will require. This allows them to respect the referendum result and avoid losing more Leave voters (or at least avoid Leave voters turning out to support the Tories) while keeping as many options open as possible once we know which scenario is playing out.