End-of-Life Care

The end of the Liverpool Care Pathway

A CHANGE IN THE SYSTEM

Last week, the publication of new guidelines on end-of-life care by NICE hailed the end of the Liverpool Care Pathway. In its place, NICE set out patient-focused guidelines that are designed to improve communication and involvement in clinical decision-making for dying patients and their families. Publishing the guidelines, NICE said that staff in England needed to move away from a ?tick-box approach? to treatment and back towards individualised care with personal care plans.

The new guidelines, which are available to read here, establish a set of parameters that staff in a wide range of primary and secondary care environments should bear in mind when a patient enters the last few days of life. These parameters cover:

- Recognising when a patient enters the end-of-life stage.

- Maintaining communication with the dying person.

- Ensuring decision-making is collaborative and shared.

- Maintaining hydration where appropriate.

- Planning pharmacological interventions (such as pain management).

A quick glance at these headings, which are broadly reflective of the NICE guidelines themselves, might suggest to the lay person that doctors do not currently take these things into account when providing end-of-life care. And rather unsurprisingly, the headlines that followed seemed to suggest that NHS England was facing an acute crisis in end-of-life care:

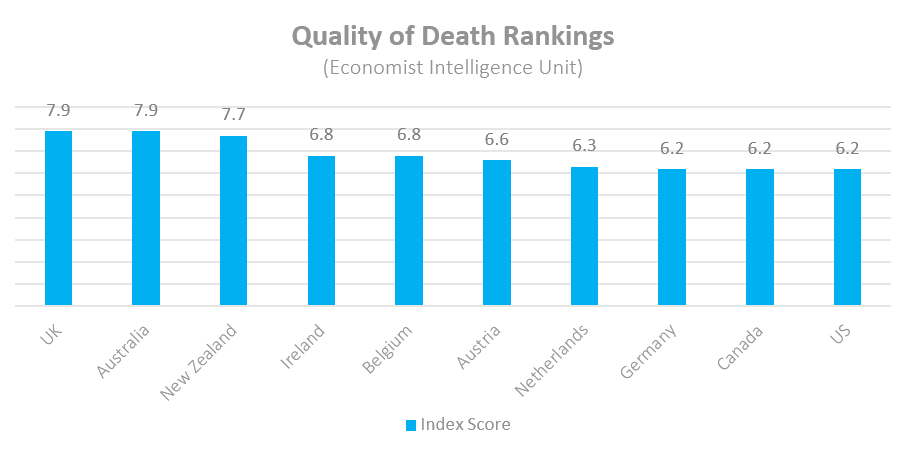

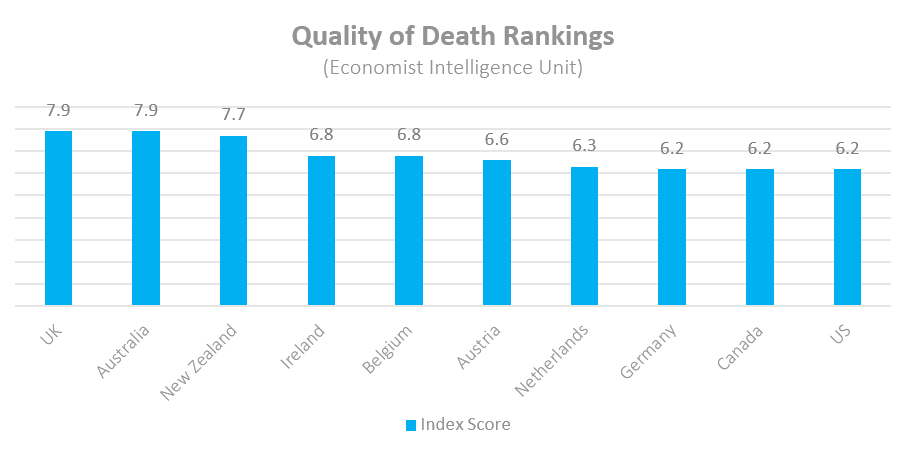

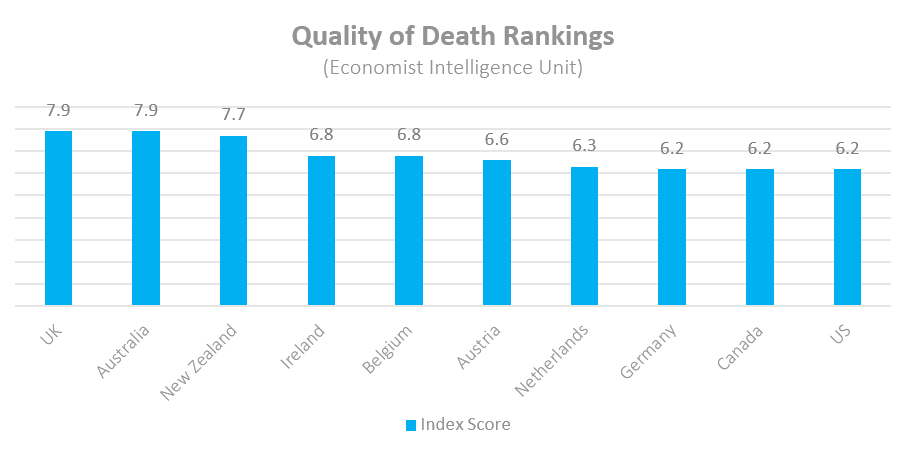

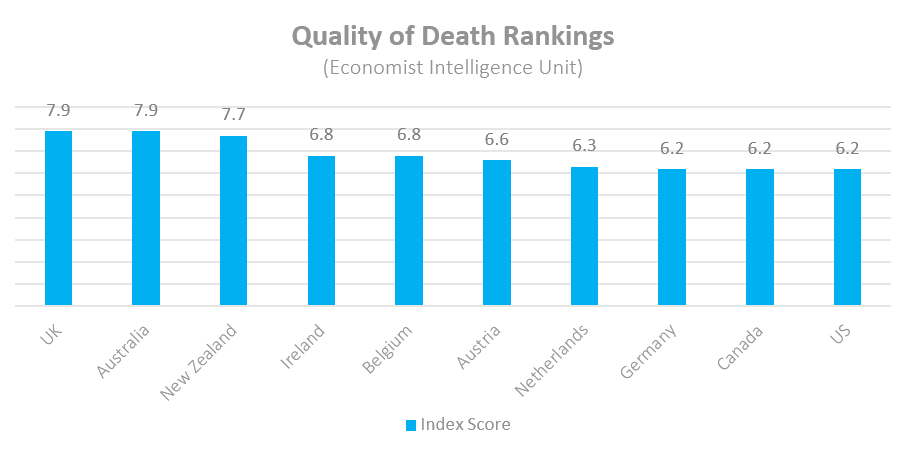

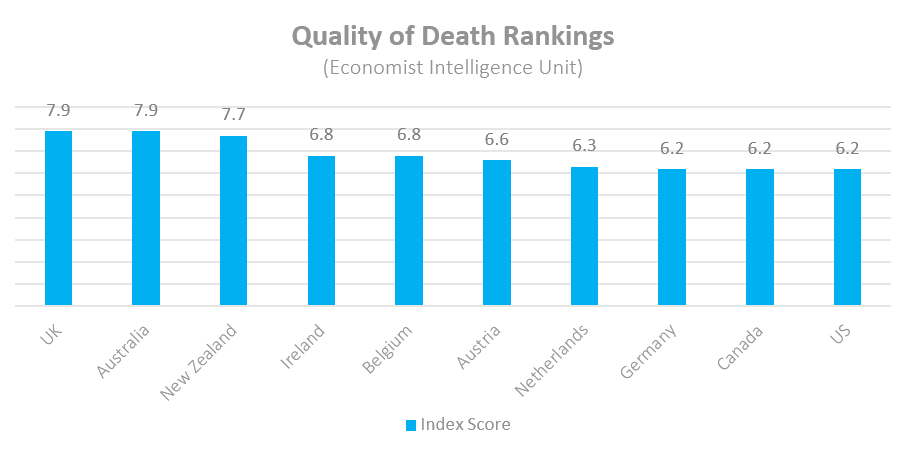

Reading these headlines, one would almost forget that only in October was the UK found to have the best end-of-life care in the world by the Economist Intelligence Unit, in which the UK received a perfect score in quality of care.

So if the quality of end-of-life care in the UK is so high, why has NICE decided to issue new guidelines ? and what should we take away from them? To answer this question, we asked nearly 450 adults across the UK to rate their experiences of end-of-life care to understand the strengths and shortcomings of the existing system.

But before we dive into the results, we first need to understand the problem.

THE LIVERPOOL CARE PATHWAY

The Liverpool Care Pathway was introduced in the 1990s ? eponymously named after the Royal Liverpool University Hospital where it was developed ? and was an attempt to take successful models of care used in hospices and develop a generic approach that would raise standards and provide uniformly good care across the health service.

It is important to bear in mind that it was introduced to standardise the level of care across NHS England. Before its introduction, dying patients were sometimes subjected to unnecessary interventions (unnecessary because they had no clinical benefit) and endured unnecessary suffering by well-meaning clinicians prolonging their lives as far as possible.

It was also introduced because end-of-life (or palliative) care is a highly specialised area of medicine, but not everyone who is required to provide it is an expert in it. In addition to palliative consultants, nurses, carers, junior doctors and others could all be placed in a situation where they need to provide end-of-life care. The Liverpool Care Pathway was designed to provide non-specialised staff a handbook to complement their clinical skills and experience and guide them through what can often be a complex and emotionally charged period in a patient?s care.

While it is generally agreed that it helped to raise the standard of end-of-life care over the past two decades, it was far from perfect. In 2013, it was the subject of an independent review that found in some cases, poor implementation of the pathway had led to disastrous care reminiscent of the Mid-Staffordshire scandal. In particular, it raised concerns over the over-prescription of painkillers, the lack of consultation with patients and relatives, and the withdrawal of oral fluids without discussion.

The review recommended the development of a series of guidelines ?that reflect the common principles of good palliative care’ and it was in this context that NICE published its new guidelines in December.

A BROKEN PATH

But just how broken is the system in the first place? To help answer this question, we asked a nationally representative sample of UK adults to tell us about the quality of palliative care that either they themselves or their relative was receiving (or had received).

More than 50% said that the overall quality of care was good ? with a quarter saying that the quality of care in their view was excellent. In contrast, 15% said that the overall quality of care was poor ? with 7% saying that the care received was terrible. While it is unacceptable for anyone to be subjected to terrible end-of-life care, whether perceived or actual, these results do suggest that the prevailing situation in the UK at the moment is one of good quality care.

Indeed, we also asked respondents to rate the different aspects of care received to understand where the shortfalls in the system may be:

These results suggest to us that the dedication and empathy shown to end-of-life patients by clinical teams is, by and large, extremely high. Indeed, the aspect of care that respondents were most likely to rate as excellent was the respect shown for the wishes of the patient and their family. This would seem to contradict last week?s headlines urging doctors to treat patients as individuals and develop personal care plans.

The most problematic area highlighted by our results was the level of integration between primary and secondary care services ? and wider social services. This is an institutional problem created by the complex layering of different services and one that the NHS and Department of Health have long been struggling with ? and which was partly the reason for the introduction of Clinical Commissioning Groups.

It is something that NHS England are continuing to explore through the development of new care models, such as the multispecialty community provider that moves specialties out of hospitals and into the community or the vanguard programme that is designed to test the benefits of different service integrations (such as urgent care integration).

The defence that could be made on behalf of doctors, therefore, is that integration is an obstacle to be overcome rather than a fault that can be laid at their feet. Part of the challenge of being a good doctor is circumnavigating organisational barriers to deliver the best care for your patient and with 44% stating that they are satisfied with the integration of services, it would seem most doctors are providing good quality care in this regard.

Arguably, where the most blame could be laid at the feet of some doctors is in the apparent lack of communication with the patient and with the family. Indeed, this was one of the key factors in the failure of the Liverpool Care Pathway in which patients were placed onto the pathway without being informed and one of the key recommendations from the review in 2013 was for hospital staff to make more time available to patients and their families:

But even as this paragraph admits, time is a resource in short supply within NHS England hospitals ? particularly in urgent and acute care settings. An ageing population, increases in the number of admissions and a lack of beds mean that doctors are not only handling larger case-loads, but also spending more administrative time attempting to safely discharge patients and secure beds for new admittances. This does not excuse some of the awful stories of mistreatment and lack of communication that surrounded the Liverpool Care Pathway ? but it does support the review?s finding that without a change in the present situation, we will continue to hear such stories as NHS staff struggle to deliver good care with fewer resources and under increased pressure.

PLUGGING THE GAP

This is exactly what the new NICE guidelines are lacking. There is no provision for a change in the palliative pathway or organisation of services around the patient and aside from the vanguard programme there are no concrete plans for how to reduce the overall pressure on the care system itself. Indeed, some doctors have even come out against the new guidelines and suggested that they are even more inadequate than the Liverpool Care Pathway itself. It makes no reference to patient nutrition, it does not add specific guidelines around hydration that were not in place before and most critically, it does not define when a patient has entered the stage of ?end-of-life? care, which is clinically difficult to define and a principal point of contention for the Liverpool Care Pathway.

Instead, these guidelines read like an interim solution ? driven by the absolutely valid notion that some guidelines are better than no guidelines at all and in the absence of any significant organisational change, guidelines are the only real option for improving the overall quality of end-of-life care. But as lay persons, potential relatives or even patients who will require end-of-life care, we need to react to these guidelines with sobriety and rationality.

New guidelines do not necessarily mean that current models and standards of care are failing patients. Neither our research nor the review of the Liverpool Care Pathway suggested a widespread failure of care. Instead, guidelines are published to standardise practice and clarify a general position on what is good and bad care. They establish a minimum standard of care rather than a maximum and do not preclude the possibility that every hospital can do better than the standards they set out. Indeed, most healthcare professionals are not tick-boxing automatons but are instead rationalising professionals who have to make careful decisions about when guidelines do and do not apply to a patient?s individual situation.

When a patient enters the final moments of their life, there will always be difficult and opaque decisions to be made. Issues that involve the possibility of patient death inexorably stretch medical ethics to breaking point and there will always be debate over the most humane and clinically appropriate course of action. But we should take solace in the fact that no matter their faults, guidelines have helped to improve the minimum standard of care ? to the point where we enjoy the best palliative health services in the world.

Rather than worry that these guidelines say something negative about our health services, we should take heart in the fact that NICE?s approach reinforces the increasingly prevalent thought in modern medicine termed values-based medicine, which places clinical decision-making within the context of the patient?s wishes and social circumstances.

In this context then, we should welcome NICE?s guidelines as an extension of people-centric medicine, which provides assurances and rights to all of us that even when we can no longer speak for ourselves, decisions will be made for us in line with our beliefs, values and wishes.

James leads the Healthcare practice at Opinium Research. If you?d like to know more about our Healthcare practice or our research in this area, please get in touch.