The warning signs of Brexit were always there

Commentators, betting markets, voters, and even perhaps the leadership of the Leave campaign expected a Remain victory in. But while the result may have been a shock, the warning signs of Brexit were always there.

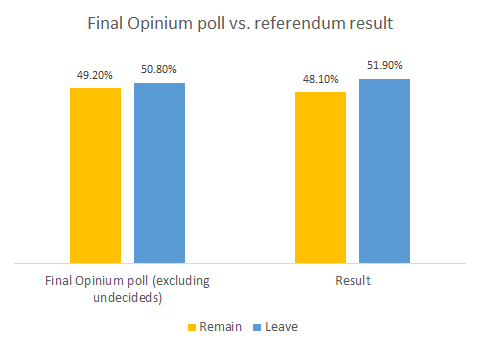

From the beginning, polls pointed to a mixed picture. Telephone polls confidently showed Remain winning while online polls consistently showed a much tighter race with Leave ahead as often as Remain, particularly for polls conducted in 2016. This led to a great deal of debate about which method was more accurate and although that question has now been answered for this occasion, the divergence allowed both sides to pick whichever results were more comforting to them and assume that they were the most accurate. Given the narrowness of Remain?s advantage, and in the penultimate week of the campaign even telephone polls showed Leave ahead, many predictions of a Remain victory relied on the assumption that there would be a swing-back to the status quo option. This happened most notably in the Scottish independence referendum when ?No? won more convincingly than polls suggested.However, in contrast with the pro-Union tilt of older voters in Scotland, older people across the UK were the demographic group most likely to be pro-Brexit. It is possible that the status quo swing-back seen in Scotland therefore was more a result of more older people turning out than younger ones and that the same thing happened this time but with the opposite result.As well as this it is possible that those over the age of 60, and thus in their late teens at the time of the UK?s accession to the EEC and 1975 referendum, saw Britain being outside of the EU as the ?status quo? and our EU membership as a 43 year experiment that should come to a close.The other factor in Scotland that helped predict a status quo vote was that ?project fear? had much more of an effect in 2014 than it did in 2016. In Scotland, 42% of voters thought independence would make them personally worse off compared to just 21% of UK voters when asked about Brexit. In contrast, 22% in 2014 said it would make no difference to them vs. 47% across the UK in 2016.As well as this, the effect of immigration in driving the Brexit vote was effectively absent in the Scottish referendum with issues of sovereignty and democracy taking a much more prominent role.Ultimately, the EU referendum result was a decision that the costs associated with reducing the levels of immigration were either illusory or worth bearing. One of the reasons that some polls failed to predict a Leave vote was because they based their assumptions about turnout among poorer voters in the North of England on a general election when these voters came out for Leave in much higher numbers than expected. This may have been harder to predict but, given the number of Labour seats where UKIP is now the main challenger, the signs were there as well.While these factors were all either known or suspected beforehand, another point needs to be emphasised. London voted to Remain by 60% to 40% and London is, coincidentally, where most commentators, national media outlets and polling companies are based. But it is not where most voters live and part of the shock at the result may be because the result was almost literally unthinkable for those of us in London. As the results show, the impact between this polarisation between London and much of the rest of the country can be enormous.

Given the narrowness of Remain?s advantage, and in the penultimate week of the campaign even telephone polls showed Leave ahead, many predictions of a Remain victory relied on the assumption that there would be a swing-back to the status quo option. This happened most notably in the Scottish independence referendum when ?No? won more convincingly than polls suggested.However, in contrast with the pro-Union tilt of older voters in Scotland, older people across the UK were the demographic group most likely to be pro-Brexit. It is possible that the status quo swing-back seen in Scotland therefore was more a result of more older people turning out than younger ones and that the same thing happened this time but with the opposite result.As well as this it is possible that those over the age of 60, and thus in their late teens at the time of the UK?s accession to the EEC and 1975 referendum, saw Britain being outside of the EU as the ?status quo? and our EU membership as a 43 year experiment that should come to a close.The other factor in Scotland that helped predict a status quo vote was that ?project fear? had much more of an effect in 2014 than it did in 2016. In Scotland, 42% of voters thought independence would make them personally worse off compared to just 21% of UK voters when asked about Brexit. In contrast, 22% in 2014 said it would make no difference to them vs. 47% across the UK in 2016.As well as this, the effect of immigration in driving the Brexit vote was effectively absent in the Scottish referendum with issues of sovereignty and democracy taking a much more prominent role.Ultimately, the EU referendum result was a decision that the costs associated with reducing the levels of immigration were either illusory or worth bearing. One of the reasons that some polls failed to predict a Leave vote was because they based their assumptions about turnout among poorer voters in the North of England on a general election when these voters came out for Leave in much higher numbers than expected. This may have been harder to predict but, given the number of Labour seats where UKIP is now the main challenger, the signs were there as well.While these factors were all either known or suspected beforehand, another point needs to be emphasised. London voted to Remain by 60% to 40% and London is, coincidentally, where most commentators, national media outlets and polling companies are based. But it is not where most voters live and part of the shock at the result may be because the result was almost literally unthinkable for those of us in London. As the results show, the impact between this polarisation between London and much of the rest of the country can be enormous.