UK: How solid is Labour’s vote share?

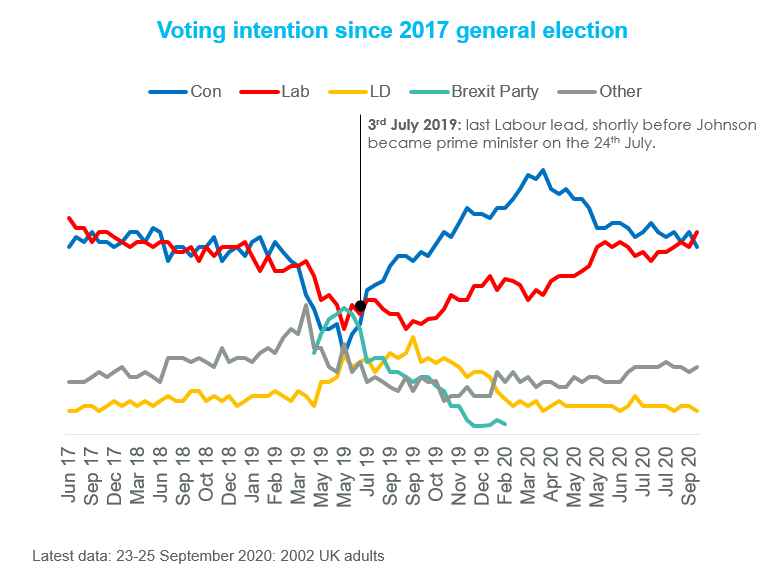

We finally have ‘crossover’ with Opinium’s first actual Labour lead since July 2019 and the change over from Theresa May to Boris Johnson. Back in July 2019 of course, we had polls showing Labour ahead on occasion but the wider context of this was both main parties haemorrhaging votes to those with more extreme Brexit positions on either side. A better point of comparison therefore may be the 2010-15 parliament in which Labour consistently held leads over the Conservatives but the Conservatives ultimately turned it around before winning an unexpected majority in 2015.

After 2010, Labour first overtook the Conservatives around the end of that year and lead for much of the parliament, peaking with a lead of around 10 points between mid-2012 and mid-2013 before started to shrink in 2014 and disappearing completely in 2015. In all of that time, however, the constant was that Ed Miliband was polling behind his party while David Cameron was polling ahead of his.

In the middle of, what was in hindsight, Ed Miliband’s polling peak as Labour leader around the 2012 party conferences, Labour were on 39% vs. 29% for the Conservatives and 10% for the Liberal Democrats. In the same poll, David Cameron and Ed Miliband both had a net approval rating of -17% but Cameron led Miliband on who would be the best prime minister (29% to 17%, 5% for Nick Clegg, 39% for ‘none of these’ and 10% for ‘don’t know’).

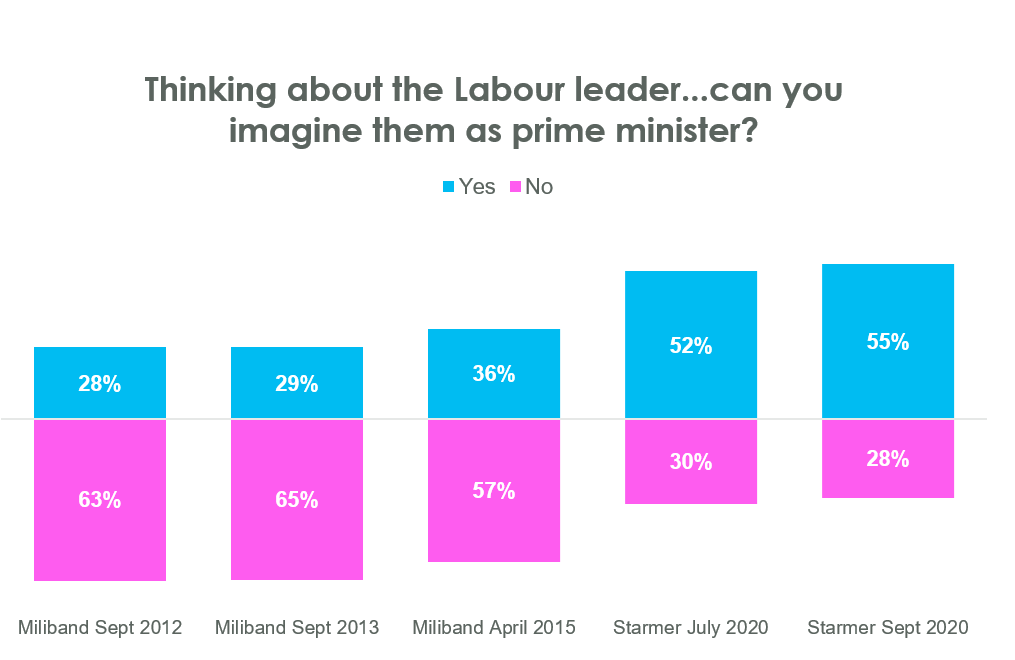

Cameron also led Miliband on a number of other measures we asked such as being capable or able to take tough decisions. Miliband only clearly leading on “in touch with ordinary peoples’ lives”, a traditional strong point of Labour leaders. But the most interesting is that this is the first time we asked voters whether they could imagine Ed Miliband as prime minister and voters said “no” by 63% to 28%.

That number improved in the 2015 election campaign, but only slightly. The equivalent question in April 2015 was 36% saying “yes” they could imagine Miliband as PM vs. 57% still saying “no”. Miliband’s “yes” figure among Labour voters had increased from 63% in 2012 to 80% in 2015 but at the same time, Labour’s share of the vote had dropped by 5 points to 34%, trailing the Conservatives on 36%.

In other words, leader approval ratings served as a leading indicator of where vote share would follow. More Labour voters thought Miliband could be PM because those who did not were no longer Labour voters.

The exact opposite has happened with Labour under Keir Starmer. Starmer’s approval ratings began in April with a net positive score of +16% (33% approved, 17% disapproved). As people made up their minds over the summer, disapproval went up but approval went up even more. In the most recent poll we have 40% approving and 21% disapproving, giving Starmer a net rating of +21%. This is down on the +30% and +28% we recorded for him in May and June but it is still comfortably net positive and ahead of Boris Johnson’s equivalent rating of -12% (47% disapproving, 35% approving).

The difference between the net and the raw figures here are important as well. Even on occasions where Miliband’s net rating was better than Cameron’s, he would be behind Cameron on the raw ‘approve’ number with Cameron’s net rating only being worse due to a higher ‘disapprove’ number. In contrast, Starmer’s raw “approval” number overtook Johnson’s in mid-May and has remained above him since.

Finally, Starmer has consistently scored very strongly on the “can you imagine him as prime minister” question that we ask about every opposition leader:

The situation is similar with the ‘best prime minister’ question. Again, Cameron would routinely lead Miliband (and, at the time, Nick Clegg) by significant margins whereas the two leaders now are typically close with Johnson and Starmer alternating the lead week to week.

None of this means a Labour victory is inevitable in a general election that is not legally required before December 2024. Similarly, the fact that Labour’s vote share has gone up does not mean that it cannot go down. However, it does indicate that Labour’s current position in voting intent, whether a small Labour lead, tied or close behind the Conservatives, is more grounded and solid than the contradictory figures we were seeing in the Miliband-Cameron days. A contradiction that, of course, ended with the leader ratings being proved correct and vote share incorrect.